The Millenials have had two defining events shape the trajectory of their ascent as a generation. The first was 9/11 and two of the longest wars in American history that followed as a result. The second was the utter meltdown of the American economy in 2008, resulting in a terrible downturn which we are only now shaking off.

In other words, the Millenials have come of age in an uncertain America, defined by turmoil, loss of prestige abroad and domestic strife. What is harder to see is that America’s recent history is also one of transition: We are living in an age of technological progress so rapid and all consuming that it’s all too easy to take the computer in your back pocket for granted. This technological explosion has rewired us as individuals and changed our perception of society. So, it is only natural that politics — which is at least partly about the interplay between individuals and society — is due for a rewiring as well.

It is easy to take things like the (relative) lack of corruption of 21st century America for granted. Things run more or less as they’re supposed to, and while corruption does exist, it is neither rampant nor invincible. In other words, corruption can and will be prosecuted in the U.S.A.

There was once a period of time where this was not the case. For more than one hundred years, the American political landscape was positively lousy with corruption. In some regards, there has been less time in American history without corruption than with it. To arrive at an understanding of American corruption, we must first look at the agent of corruption — at entities known as political machines. These groups were largely responsible for the age of graft and inefficiency in American history. Lest you assume that these entities did not significantly affect American politics, know this: Political machines were often responsible for the political careers of mayors, congressmen and senators, as well as presidents. Harry Truman was a beneficiary of machine politics, as were most of the presidents from the end of the Civil War to the time of Theodore Roosevelt almost 40 years later. The change wrought by these groups is weighty indeed.

Machine politics are somewhat difficult to define. Think of a traditional political party, like the Democrats or Republicans. These parties are tasked with finding candidates, running and funding campaigns, and coordinating a platform, or set of values the party ostensibly stands for. Now think of a traditional party, but with extra parts grafted on to it. These parts can range from efforts in community outreach to blackmail, bribery, vote rigging and the policy of rewarding supporters of the machine with jobs for which they are unqualified. Corruption is a natural byproduct of these machines, similar to how carbon dioxide is a byproduct of respiration in humans.

For all the graft and corruption that these groups cause, there were also tangible benefits to machine politics. For one, political machines enfranchised entire ethnic and religious groups, many of which were recent immigrants. In other words, the politics of the machine helped elevate immigrants who might not otherwise have risen to prominent positions. Further, machine politics made ordinary people feel less powerless against the monumental forces of the day, and acted as a buffer from the harshness of the times.

Many of the contexts that gave rise to machine politics in the nineteenth century are present in 21st century America.

Political machines were able to rise to such a powerful place because they capitalized on the changes of the day, change that drove new political ideology and practice, change that saw the rise of cities and new demographics, and change that ultimately drove people into groups of like-minded individuals.

It is a tired cliche that history repeats itself. As it is commonly used, its meaning has shifted to mean something more definite than the phrase is intended to mean. History does not repeat itself, at least not perfectly or entirely clearly. Instead, the past merely harmonizes with the present, and certain themes can be present across vast gulfs of time. In other words, certain contexts may arise in a present time, contexts that gave rise to movements in the past and will almost certainly do so again. Those movements may run parallel to their predecessors, or they may run counter to them. Contexts arise, people react.

With that in mind, many of the contexts that gave rise to machine politics are present in 21st century America.

America finds itself once again in a time of rapid transition, brought by technological advancement and a changing understanding of the nature of the political and of the market. This has caused and hastened sweeping demographic changes, creating intensely loyal and reactionary groups of like-minded people. These contexts will generate a movement within society, impacting American politics and consequently affecting history. Though the new era will likely not lead to as much corruption, similar understandings of political strategy could very well occur.

The roots of machine politics go back to almost the minute the republic was born. It seems strange to us now, but there was time in America when political parties simply did not exist, though that era, as will presently become clear, did not last for very long. In 1796, George Washington wrapped up a largely uneventful second term with a warning: political parties were dangerous, full stop. As Washington saw it, political parties bred only dissolution and strife, encouraging an us-versus-them mentality that could only bring harm to the newly formed republic.

Unfortunately, Washington’s compatriots couldn’t hear the message for all the bickering between themselves. A major dispute broke out amongst the political elite concerning America’s future direction, with two major camps vying for supremacy. First were the federalists, headed by the brilliant but extremely arrogant Alexander Hamilton. The other, headed by Thomas Jefferson, was the Democratic-Republican Party. At Jefferson’s side was a man named Aaron Burr, a man with an extreme temper and a palpable hatred of Federalism.

Political maneuvering, borderline-at-best legal methodology, and the odd dose of violence — these are the things machine politics are made of.

Burr was a clever political tactician, and in the 1800 election, Thomas Jefferson agreed to take Burr on as vice president if Burr could secure New York for him. To accomplish this, Burr approached members of a group known as the Colombian Order with a plan. The Order, made up of prominent people, was largely social club, not unlike a fraternity. Burr used the Order’s considerable clout to help swing the election, and in 1800 Burr became Jefferson’s vice president. In the process, the social club was transformed into a political organization, known as Tammany Hall. Thus, the first political machine in American politics was brought into existence. As for Burr, he is perhaps best known for shooting and eventually killing Alexander Hamilton in a duel, extinguishing the man behind the Federalists and the figure on the American $10 bill, but he also had a fairly distinguished career of plotting to overthrow the government. Political maneuvering, borderline-at-best legal methodology, and the odd dose of violence — these are the things machine politics are made of.

Tammany Hall lurked behind the scenes for a long while, finally bursting forth in 1855 by electing the group’s first mayor of New York City. It was a breakthrough that would make the city theirs for the next 70 years. That’s 70 years of controlling projects, appropriating funds, silencing opposition and living the good life.

So how did political organization like Tammany Hall go from powerful, but largely localized, political groups to muscular political juggernauts?

The key was transition, an era of change unlike anything before, in which every aspect of daily life was uprooted and transformed. Three simultaneous revolutions drove this transformation: industrial, market and transportation. The world suddenly became smaller as the advent of the railroad, better roads and a vigorous postal service all served to foster better communication. Great wealth was created, especially in the cities and factory towns. Work, especially in the North, became much more refined and efficient, helping generate more wealth. For all the positives, this period of transition was absolutely shot through with turmoil. Worker riots became commonplace, unemployment reached epic proportions in some parts of the country, deplorable living conditions became the norm in overcrowded cities and entire trades were shut down or reorganized into something unrecognizable. On top of all this, another turmoil was also an additional wrinkle: massive immigration by Irish and German peoples. These immigrants were met with callous indifference at best and violent hostility at worst, and were seen as workers who would steal already scarce jobs from “American” citizens.

It was also a time of political upheaval. Andrew Jackson, one of the most outlandish and insane figures in all of history, shattered notions about the limits of presidential power. He routinely pushed the envelope of what was politically possible when he wasn’t quelling would-be southern revolts, beating would-be assassins senseless with his own cane, oppressing Native Americans, or dueling people he disliked — a list that was very long indeed. It wasn’t just Jackson — his followers were many, and they were as zealous in their reinterpretation of political tradition as he was. It is no coincidence that Andrew Jackson’s Presidency saw the rise of organized political parties, finally killing, once and for all, George Washington’s dream of a factionless republic. One of the most important political changes wrought by Jackson’s followers was the new idea that government jobs now belonged to whichever party was in control of government. This was known as the spoils system, according to a natural political principle that one Jacksonian lieutenant summed up as, “To the victor belongs the spoils.” As a direct and almost immediate result, corruption ran rampant.

As a possible result of these changes and a future made uncertain, a curious trend occurred in America. The mid-to-late 19th century saw an incredible rise in social groups, from the secret societies of the Ivy League to orders like the Freemasons, which proliferated across the country, but especially in the cities — among the many groups were organizations that later became the modern basis for Greek Life. Two groups in particular stand out as a creation of and reaction to the changing times. The first is an order known as the “Know-nothings.” The group was extremely anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant, and counted amongst its members an American President, Millard Fillmore. The other group was Tammany Hall. Irish immigrants were able to gain entry to American politics via the machine, and were able to wield enormous clout. In many ways, Tammany Hall served as an important naturalizing force for recently arrived immigrants, who often received tangible benefits from the machine in return for their votes. The connections and loyalty to these groups in this era are difficult to underestimate.

By winning the loyalty of immigrants and by seizing upon the benefits of the spoils system, Tammany Hall was able to navigate the time of uncertainty in the mid-nineteenth century to their advantage. Following the chaos and destruction of the Civil War, president Ulysses S. Grant’s administration provided even greater chances for corruption. A decisive general, but a drunken and near-sighted president, Grant’s administration was rocked by scandal after scandal. In New York, possibly the greatest of all the Tammany Hall bosses ruled the city: Boss Tweed.

The Progressive Movement finally restored a sense of balance to an America thrown off kilter by the earlier time of transition and Civil War.

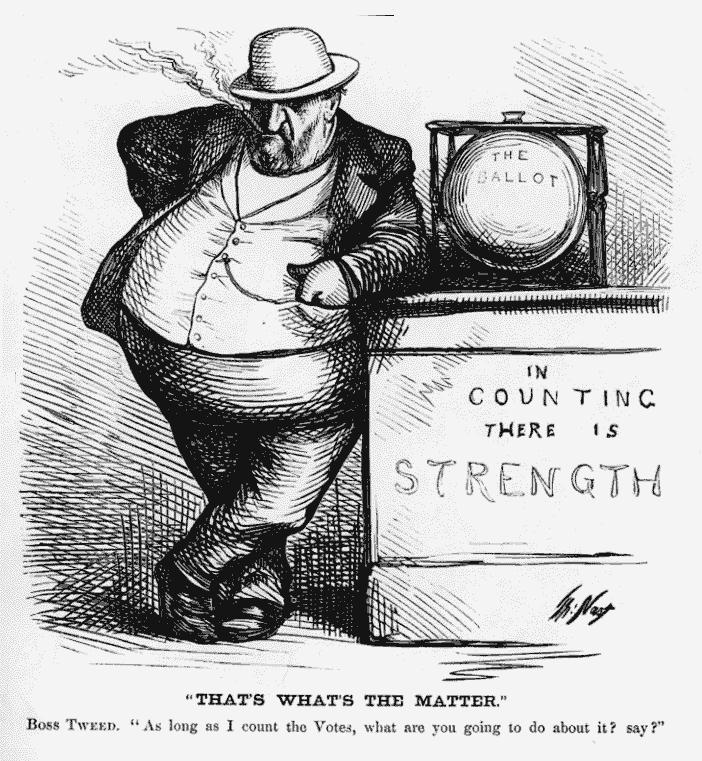

Tweed was an immensely powerful man, but his power attracted the ire of many people, and a new movement began stirring in the wings. Tweed was attacked on many fronts, but it was the pen of a man named Thomas Nast who did him the most harm. Nast was a talented illustrator and satirist, akin to Jon Stewart or Stephen Colbert. Nast routinely targeted Tammany Hall and Boss Tweed in his imagery, which was powerful and iconic. Indeed, the modern depiction of the Republican Party as an elephant and the Democratic Party as a donkey came from Nast’s illustrations — The donkey was an insult to the Democrats, the party of Tammany Hall and southerners who resented the North, Lincoln, Reconstruction and equality before the law. It’s an insult that has long since been stripped of its potency and adopted by the mainstream as a symbol of the left. There were others besides Nast, including the lawyer who eventually toppled Tweed. The organization would live on and grow strong once more in time, though not for long.

It was not just the district attorney who stood up in this time. Across the nation, a movement was building to destroy machine politics. A young Theodore Roosevelt cut his teeth in the New York Assembly battling Tammany Hall, and others like him became commonplace. Eventually, this would blossom into the Progressive Movement, which finally restored a sense of balance to an America thrown off kilter by the earlier time of transition and Civil War. As a result, the power of machine politics was largely degraded and eventually eliminated, a memory of a previous era.

There is change in the air again. In about 20 years of existence, the Internet has infiltrated every facet of America, in much the same way that the industrial and market revolutions did in the mid-19th century. In that same span of time, globalization has only grown — the world is more interconnected and more interdependent now than ever before, and every day, the internet and communications revolution accelerates that process. With change comes turmoil. While employment and desperation are not nearly as bad as they were in a previous age, cracks are showing. Transition, like the one before, breeds a feeling of impotence. The Occupy Movement and the Tea Party are ultimately two different sides of the political spectrum expressing a similar discontent with forces seemingly transcendent.

In our time, when half of America is afraid of what we are moving towards and the other half is convinced we are not getting there fast enough, the power offered by machine politics is tantalizing.

Indeed, the rise of such groups and the loyalty to those groups are going nowhere. Social media, as well as the general fracturing of America’s nationalism following the end of the Cold War, has largely driven us into clans of like-minded people, creating vacuum chambers in which we hear only what we want to hear and believe only what we choose to believe. The current Measles outbreak in Disneyland that resulted from a group of people who chose not to vaccinate their children is a particularly dramatic example of this phenomenon. It is in such a climate that machine politics become an appealing option.

First, as I have tried to show in this article, political machines are able to seize on new political ideas and refine them. In this era, I would posit that the Citizens United Supreme Court decision and new attention to campaign finance represent a bold new frontier into which we’ve only (unfortunately) just begun to explore, a frontier that will likely determine political organization for the foreseeable future. Second, the rise of factionalism creates an us-versus-them mentality that ultimately justifies the negative aspects of machine politics. Finally, and most importantly, the machine itself provides an identity to the newly arrived and disenfranchised groups in America, a chance for a recapturing of power against forces seemingly beyond our control and acceptance. In our time, when half of America is afraid of what we are moving towards and the other half is convinced we are not getting there fast enough, the power that machine politics offer is tantalizing.

It is also likely that whatever replaces the new machine politics era of American politics will be the one that simultaneously balances the contexts that created machine politics in the first place. For all the action that Progressives directed towards machine politics itself, much more of their action was directed against the negative aspects of the industrial and market revolution. In short, Progressives were able to degrade machine politics by mitigating the external factors that allowed machine politics to thrive in the first place. The rise of machine politics has many negative drawbacks, but ultimately this style of politics serves an intermediary phase from the beginning of a transitionary era to when we’re finally able to reconcile those changes.

As interesting as all of this may be, who cares? The people who will have to decide what the future of politics are Millenials. We can choose machine politics to shelter us and curse America with decades of inefficiency, or we can choose to mitigate the factors that allow machine politics to look like a good option in the first place.

Collegian Columnist Jesse Carey is all about disrupting the lame-stream media narrative, except for when it suits him, and can be reached at letters@collegian.com or on Twitter @Junotbend.